In 2017, Maughn Gregory, the director of the Institute for the Advancement of Philosophy For Children (IAPC), published a crucial article in Routledge’s International Perspectives series, History, Theory & Practice of Philosophy for Children. On reading it, I acknowledged that my knowledge of philosophy for children (P4C) is as nothing in comparison to those researching and teaching in the area.

More importantly, I’m mindful of positioning my passion for bringing philosophy to middle school students in respect to what Maughn Gregory calls the “new phenomenon of branding, in which individuals and organisations advertise new and supposedly unique approaches to P4C.” (2017, 210)

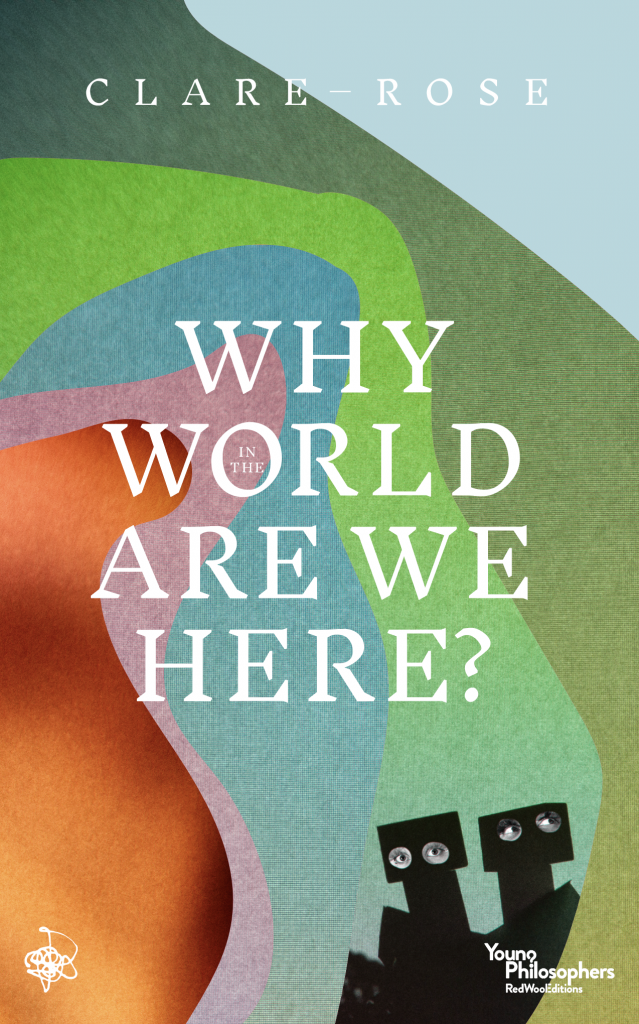

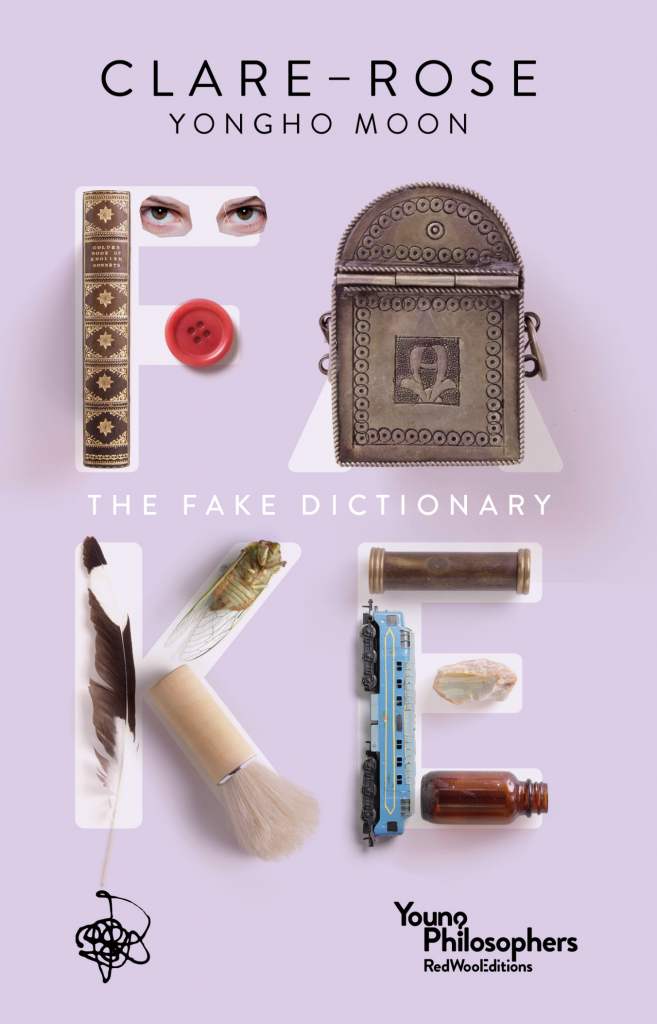

Consequently, I admit from the outset that that is exactly what I’m doing with Red Wool Editions’ Young Philosophers Series. The collection of four short books, pictured below, are authored by Red Wool Editions founder, Clare-Rose Trevelyan, and illustrated by Yongho Moon. Their aim is to enable 9 to 13-year-olds to have philosophical conversations with parents and teachers.

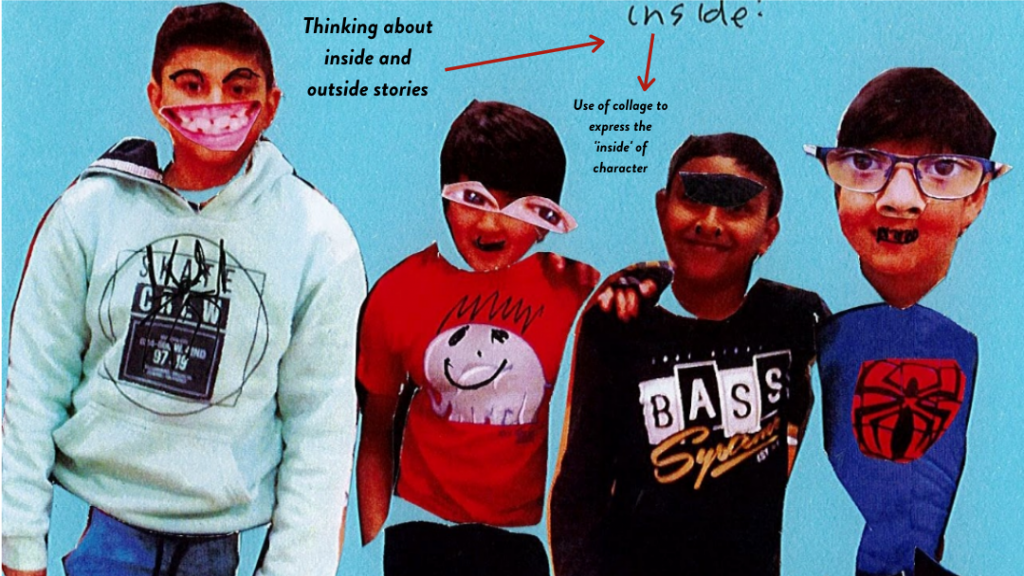

I have been working with Clare, Yong and book designer Francis Lim on the project since 2016. We are now ready to launch programmes and projects in schools. In essence, this means for me prototyping activities that ‘deconstruct’ the P4C methods I was introduced to in 1996 by Dr Felicity Haynes at the University Western Australia. We will have our first opportunity to share our work with colleagues at the Victorian Association for Philosophy in Schools conference in July 2020.

Discovering our direction

Maughn Gregory states in the early part of his paper that, in the fifty years since Lipman first launched Harry Stottlmeier’s Discovery, there have seen ‘diverse and divergent approaches’ to P4C around the world. Of particular interest to me is his observations on Shaun Gallagher’s four categories of hermeneutics – conservative, critical, radical and moderate – to analyse approaches to P4C. He writes

Gallagher identifies teaching for critical thinking as a conservative hermeneutical agenda and there are those in P4C who value it primarily as a thinking skills program. Critical hermeneutics sees interpretation as the work of liberating the reader from ideological biases such as white supremacy and patriarchy, and there are those who see P4C as a means of waking students up to the power or such ideological forces in their lives. Radical Hermeneutics sees interpretation as expanding the plurality of meanings and resisting attempts to reach objectivity or consensus, and there are those in P4C who practice it as a pedagogy of disruption.

Gregory, M (2017) Where are we now? in Saeed Naji and Rosnani Hashim (eds) History, Theory and Practice of Philosophy for Children, Routledge, Oxford, UK, p.210

I hold these distinctions in mind for three reasons with regards to our Young Philosophers Series. The first is in an attempt to place philosophy at the centre of a school curriculum, an objective which takes account of why P4C, according to Professor Gregory “still strikes many as odd and in need of special justification”. Secondly, I wonder what would happen if philosophy was geared up for the most disengaged students in the school system. These are customarily found in middle school, in the transitioning years between primary and secondary school.

And thirdly, I feel I am old enough to observe (after 40 years in education) that, while I don’t have empirical data, my own classroom experiences have shown me how philosophy is a vital context for enabling students to develop the multidisciplinary learning outcomes, known today as capabilities or competencies. It’s not lost on me how these ‘overarching outcomes’, which include thinking skills, ethical, intercultural, personal and social understanding, now have a renewed focus through the ‘future of work’ movement in schools globally.

I know these things as a writer of curriculum frameworks too

Before living in Victoria, I wrote outcomes-based curriculum frameworks in my home state of Western Australia. Consequently, I know from the implementation phase of curriculum reforms that teachers do not find it easy moving from subject focus outcomes to multidisciplinary ones. The more conscientious teachers spend an eternity forensically unpacking the concepts, skills and processes of learning outcomes, while others are happy to generalise.

Again, speaking from my own experience, the truth is that while the reform to outcomes-based education turned the old teacher-centred system on its head, we rarely invested time as educators to philosophise around the the ‘nuts and bolts’ of how we packaged knowledge and social experiences in our classrooms. It is only now, 20 years on, that I’m game to say that assessing student-centred outcomes-based learning is staggeringly complex.

So, while I understand that Professor Gregory qualms about the commercialisation of philosophy for children, I wonder what he thinks about the huge business which has arisen around educational assessment? Has he considered that perhaps a major reason why only a “small number of schools” conduct a P4C approach is that it has not been incorporated into measuring the difference it makes to the student’s achievement of generic competencies?

Student achievement through the Young Philosophers Series

What’s left for me to do then, I believe, is to use Professor Gregory’s succinct five-stage outline of Lipman’s and Sharp’s Community of Inquiry method, in considering what we are offering schools. How close or divergent it is from the approach, no doubt will be noted in good time.

Furthermore, as a curriculum writer, I’m taking these stages and interrogating them through some key texts which have influenced the ‘rolling out’ of P4C over the years. I include in these Professor Gregory’s 2017 references.

However, as you might imagine, devising a new programme is by its name experimental. So, it may be interesting to firstly share with readers the principles which have emerged for us as we prototype the programme with schools. Then, in my readings specifically include the study of:

- Lipman, Matthew & Sharp, Ann Margaret, 1942-, (joint author.) & Oscanyan, Frederick S. (Frederick Stone), 1934-, (joint author.) (1980). Philosophy in the classroom (2nd ed). Temple University Press, Philadelphia

- Matthew Lipman – Thinking in Education, 2nd Edition (2003)

- Splitter, Laurance & Sharp, Ann Margaret, 1942- & Australian Council for Educational Research (1995). Teaching for better thinking: the classroom community of inquiry. Australian Council for Educational Research, Hawthorn, Vic

- Joanna Haynes – Children as Philosophers_ Learning through Enquiry and Dialogue in the Primary Classroom (2001)

- Ann Margaret Sharp, Ronald E. Reed – Studies in Philosophy for Children_ Harry Stottlemeier’s Discovery-Temple University Press (1991)

- (Routledge International Studies in the Philosophy of Education) Tim Sprod – Philosophical Discussion in Moral Education_ The Community of Ethical Inquiry -Routledge (2001)

- (Foundations of Education Studies) Joanna Haynes, Ken Gale, Melanie Parker – Philosophy and Education_ An introduction to key questions and themes-Routledge (2014)

Stage 1: The offering of the text [Students read or enact a philosophical story together.]

Stage 2: The construction of the agenda. [Students raise questions for discussion and organise them into an agenda.]

Stage 3: Solidifying the community [Students dialogue about the questions as a community of inquiry facilitated by an adult with philosophical training. Discussion continues over subsequent philosophy sessions until the agenda for the reading is finished, or until the students agree to move on to next reading.]

Stage 4: Using exercises and discussion plans [The philosophical facilitator introduces relevant activities to deepen and expand the students’ inquiry.]

Stage 5: Encouraging further responses [These include, e.g., self-assessment of philosophy practice, and the expression and further exploration of philosophical judgments in art projects, creative writing, dramatic role-play, etc.]