The EducationHQ News Team presents an interesting article on classroom teacher Benjamin Kilby who is researching the Philosophy for Children (P4C) method. Mr Kilby is most interested in enabling gender-equitable dialogue. As the treasurer of the Victorian Association of Philosophy in Schools, he is also at the forefront of the advocacy group that beings the methodology into all schools.

My introduction to p4C

Dr Felicity Haynes at the University of Western Australia gave me a great introduction to philosophy for children or P4C as a global phenomenon in the early 2000s. At the time, I was running an arts centre and I was keen to devise drama, technology and philosophy links within our programs.

Twenty years later, it’s disappointing to read that, according to Ben Kilby, philosophy for children is still largely unfunded in Australian schools. Consequently, “any teaching of the subject is usually reliant on an individual teacher with a passion”.

I worked with Western Australian colleagues from 2002 to 2007 under the same conditions which he describes for Victorian schools. My conclusion was that the greatest reason for the lack of uptake was the time-factor. In my experience, teachers interacting with philosophy for children seemed to work best when they were as delightfully engaged with a community of enquiry as they are to their students.

philosophy for children need not be an added extra

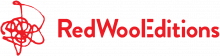

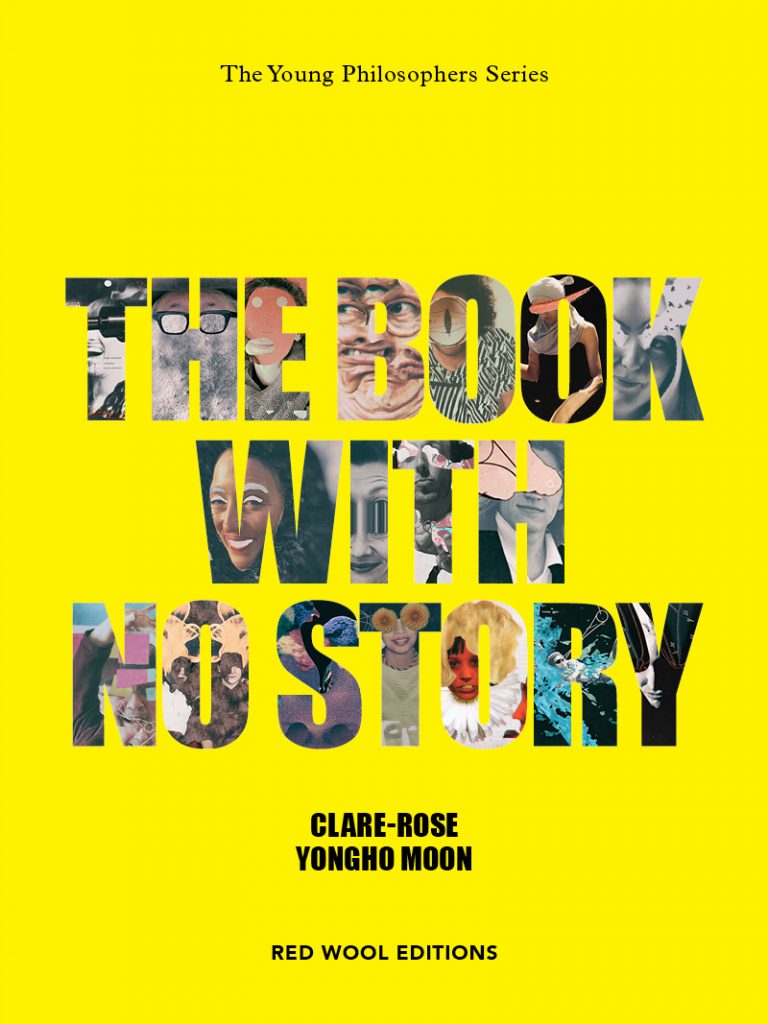

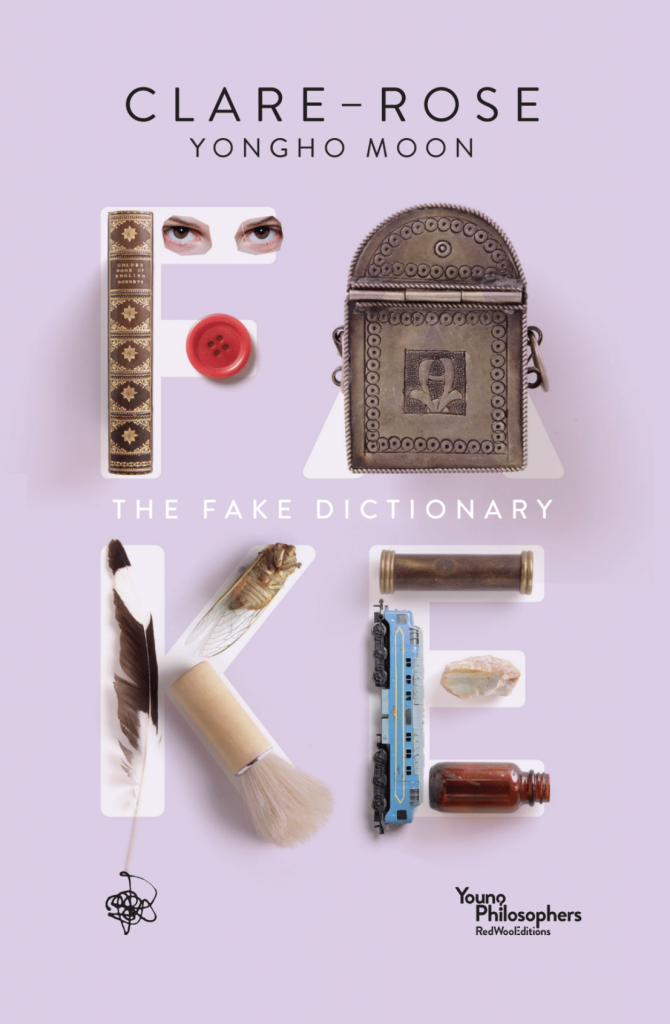

Today, our creative team put their talent and investment into producing the YOUNG PHILOSOPHERS SERIES. This is a series of small books by author Clare-Rose Trevelyan designed to get young people questioning, talking and writing.

I’ve written about the books in other blogs on viewing children as philosophers and championing them as imaginative young writers too.

Nothing like the real thing – A Morning with P4C

On Wednesday 20 November, the author and I shared our approach with Year 6 students at Wooranna Park Primary School. The Victorian Association of Philosophy in Schools features WPPS on its website for the association’s work in Melbourne’s Southern Hub. We worked in the Da Vinci Centre classroom, a wonderful space in the school library. The atmosphere perfectly reflected the imaginative yet rigorous approach of librarian Debra Nugent. Debra works with two groups of Year 6s on Wednesday morning between 9 and 10.30 am.

The sessions went something like this:

- We began by showing a pile of Clare’s books and explained to the children that in the process of writing the stories, Clare noticed characters and creatures running away from her. She discovered that they found her stories boring, particularly the endings. So, they left hoping to meet fresh young minds who would put them into new stories.

- Nonetheless, Clare managed to collect 52 of the runaways and put them into a small book which she called The Book With No Story. She figured she would help the characters find children who have the freshest minds on the planet. She would ask children what they could make of them.

- So she had Yongho Moon illustrate something of what the creatures looked like. Meanwhile, she would write the best descriptions she could in an inside-out kind of way. That is, she would put together something about their ‘inside’ feelings and their ‘outside’ appearances.

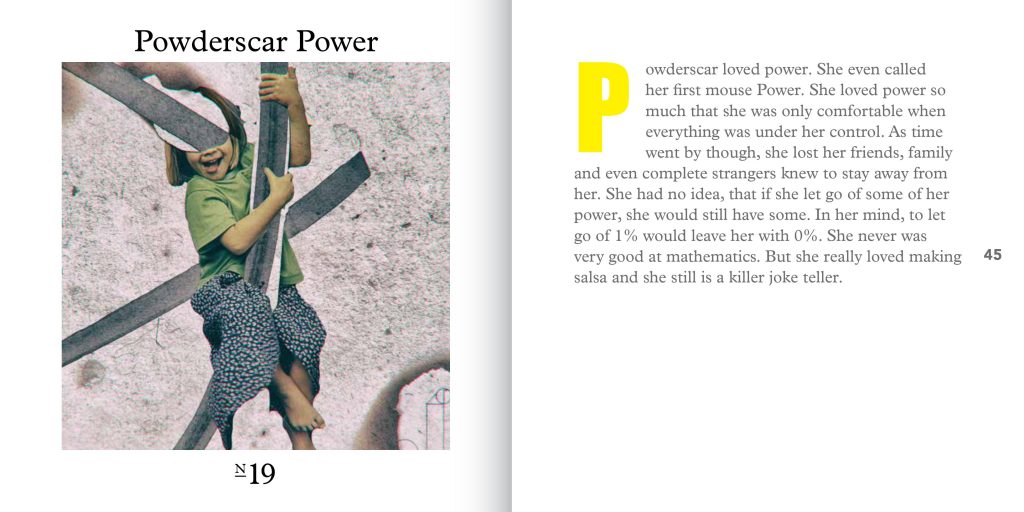

- At the beginning of the workshop, one group of Year 6s looked at different creatures while the second group just focused on just one- POWDERSCAR POWER.

- Both groups took turns at reading the character description and probing the meaning of the name and the ‘big idea’ being communicated. However, we believe the group who began with a collective approach through Powderscar Power seemed to tap into the skills which they had learned through questioning and the P4C approach more effectively.

Philosophy for children takes off in an embodied way

With Mrs Nugent’s kind advice, we related asking questions to the research the Year 6s were doing in Australian history. We were able to affirm our view that curiosity happens within a moment in time for young philosophers. For instance, how Sierra focused on what happened when the first settlers in Botany Bay encountered Aboriginal people? Similarly, how Stefan discovered when the bushranger Moondyne Joe was first imprisoned in England?

Remarkably, curiosity about a fictional character can begin through their name and their overwhelming feeling they bring up in the reader. Powderscar loved power. From that point on, so many questions arise. Why does Powderscar only feel comfortable when everything is under her control? What is power anyway? Who has it and who doesn’t? How does mathematics come into understanding power?

[ngg src=”galleries” ids=”7″ display=”basic_imagebrowser”]What happens next in our participation with philosophy in schools?

We left behind images, descriptions and books so that the Year 6s might continue to do some thinking about curious creatures and their own curiosity about them. We plan to return in a fortnight and look at the questions from another viewpoint. This time from taking a deeper look at the collage-style images.

Unlike traditional portraits, the creatures illustrated in The Book With No Story are revealed in collage-style. For thinkers, understanding what images reveal is as much about what is not in the picture as what they see. They must imagine what’s around the image. How does it fit into the story of the character?

Clare, Yong and I are looking forward to working in the visual arts studio in the Year 6 area and continuing to view matters through the eyes of young philosophers.